Robbed of their chance to bid final farewells to their close ones

An Evacuation.City journalist spoke with several relatives who escaped abroad, robbed of their chance to bury their close ones. People shared their memories and spoke about their losses and plans for the future that was never meant to be.

My beautiful life turned heroic: story of an intelligence officer from Kharkiv

The Bezuhliy family: Oleksandr, Kateryna, and their kids.

The Bezuhliy family: Oleksandr, Kateryna, and their kids.

Oleksandr Bezuhliy, an intelligence officer and a co-founder of Kharkiv’s Territorial Defence, fell in combat in Kharkiv on March 3. It took quite a while to recover his body, and only on March 19, his death was confirmed.

His wife Kateryna and their two children, son Oleksiy and daughter Anna learned about their loss from Poland. They never got to bid their final farewells to their husband and father, so to them, he’s forever alive and smiling.

Bezuhliy family’s pre-war life

Before February 24, the Bezuhliy couple had a happy, active life in Kharkiv.

Oleksandr, an intelligence major, was a man of many talents. Aside from his military career that he had embarked on in his final years of life, he had been a lecturer of a Regional and Local Governance Department at Kharkiv Karazin University, and one of the facilitators of Kharkiv Studrespublika. Oleksander’s projects and activities were so plentiful that one can speak about them for hours.

In his student years, he met his wife, Kateryna, at a bard song and poetry festival.

“We were inseparable ever since, married for 19 years. He had been my everything: my beloved, my friend, a great dad to my children,” recalls Kateryna Bezuhla.

Kateryna is a vocalism instructor. To help her, her husband learned the intricacies of musical equipment and equipped a studio for her all on his own. He also helped her while she was pursuing her Master’s degree at a Conservatory.

Oleksandr Bezuhliy and his family.

Oleksandr Bezuhliy and his family.

“He used to always tell me that we had to live our lives in the moment, without putting anything off for later. He loved spending time with our children and took them to various extracurricular activities. Our daughter had dreamt of having a treehouse, so he built it in just one day. This winter, he fulfilled his — our — dream and took the whole family on a trip to the Carpathian mountains,” recalls Kateryna.

Your safety is what matters to me: early days of full-scale invasion and evacuation to Poland

When the full-fledged war broke out, Oleksandr put his wife, daughter, and son in a car, drove them to her parents’ in Kharkiv Oblast (region), and then left to run his military errands. He instructed that his family continued to move further West.

“Our safety was his main concern,” says Kateryna.

So the mother and her children first evacuated to Oleksander’s friends’ place in Central Ukraine, and later, one of Kateryna’s students invited them to her home in Poland.

On the night of March 2nd to 3rd, Oleksandr Bezuhliy reported for duty. Around 10:15 p.m., the Russians launched a powerful rocket attack on the local ground defense headquarters. In that bombing, Olexandr’s comrades were wounded, and the man himself, who happened to be in the epicenter of one explosion, was killed.

Oleksandr was out of reach since a few days before his death, yet since interrupted communication had always been a possibility, the man took care to provide his family with reliable emergency contacts should he have stopped responding.

It was Oleksandr’s parents, Tetiana and Volodymyr, who took care of his funeral proceeding, assisted by the Military Commissariat. They persuaded the widow not to come from Poland for his funeral so that her last memory of him would be the one where he was alive and smiling.

“My mind made that difficult decision, yet my heart, of course, failed to accept it. That is why the pain of not being able to bid my final farewells remains with me forever,” the woman says, sadness in her voice.

Oleksandr Bezuhliy found his final resting place in the Ally of Glory of Kharkiv’s cemetery #18. Kateryna has plans of returning to Ukraine in August, to see her family and bid her farewell to the love of her life and the father of her children.

“When I learned about his death, I didn’t try to withhold the truth from my children. I told them that their dad had become an angel and be watching out for us from the skies,” says Kateryna.

Oleksandr was also known for his other talent: he was a great storyteller, and children just loved hearing his tales and his stories about him growing up. One night, when putting his kids to bed, he told them a tale about a little steam train’s adventures that he made up on the spot. He went along with every stage of his children’s lives, becoming more mature himself as they grew older. He had his challenges, gains, and failures before his life was cut short by the war.

In his final days, Oleksandr gave his wife access to his personal journal called “My Beautiful Life” where he kept a record of the happiest moments of his life. One of his final entries said, “I want to be a hero.”

Three deaths in one day: the story of the Plokhykh-Rostovskiy family from Mariupol

The Plokhykh family.

The Plokhykh family.

Tetiana Plokhykh, her daughter Varvara and her mother Zhanna were killed on March 14, during another bombing of Marioupol’s residential buildings by the Russian military. Of the entire extended family, the only ones to survive were Tetiana’s husband Illia, their oldest daughter Karina, Tetiana’s sister Olena Rostovska and her daughter. It was Olena, who evacuated to Greece, to tell us the tale of how her close ones were killed.

The sisters’ pre-war life

Just like millions of Ukrainians, the Plokhykh-Rostovskiy family lived an ordinary life until February 24. A 38-year-old Tetiana Plokhykh worked as an administrator and a saleswoman at Anabel Arto lingerie store. With Illia, her husband of 12 years, she was raising their two daughters, a 13-year-old Karina and a 9-year-old Varvara.

“Everyone adored Tetiana. Despite her working at a small store, people used to stop by all the time, not least because of her skill in helping her clients. A cheerful and vibrant person, she didn’t like to sit around and traveled often. Her family was her top priority, it is for them that she was earning her income,” tells Olena, tears in her eyes.

The sisters saw each other often and visited one another at their homes. Olena lived with their mother, Zhanna, in one of Mariupol’s downtown neighborhoods, while her sister ran her own household.

I learned about the war from my friend from Greece

Olena Rostovska is on maternity leave. On the morning of February 24, she was scheduled to take her daughter to her daycare, where a recital was to be held:

“ That morning, a friend from Greece called and told me that the hostilities began. I was in denial at first, I mean, it was so quiet outside. Another hour went by, and the daycare worker called and told me not to bring my daughter that day ‘due to the war’.”

After some time, Olena and her mother Zhanna heard explosions. They immediately called their sister and daughter, Tetiana, and the three women decided not to panic, hoping that the shelling wouldn’t last long and that it would be all right again after that. In 2 or 3 days, according to Olena, the grocery stores in the city were empty, so one couldn’t buy anything. Then the electricity was gone, and small convenience stores ran out of operation. There was no food in the city anymore. Along with the electricity, tap water, gas and heating were also cut off. People started extracting the remaining water from their pipes, and boilers. There was a kindergarten nearby, and people lined up and waited for their turn to extract some technical water from the facility’s pipes. They used that as their drinking and cooking water.

Olena Rostovska, Zhanna Rostovska, and Tetiana Plokhykh.

Olena Rostovska, Zhanna Rostovska, and Tetiana Plokhykh.

Immediately after the full-scale war broke out, Olena and her mother moved in with their in-laws, Illa’s parents, thinking it was dangerous to stay in their 9-story building. Their unit was situated on the second floor so, should the building collapse, they would be doomed.

Olena says that very soon Mariupol went into a total blackout. There was no cellular service or other means of communication, and they were shelled and bombed daily. People went out to melt some snow, make a fire, and cook something over it.

The day you both remember and fail to remember

The woman has a hard time recalling the events of March, 24; she learned most of them from her brother-in-law, Illia. Sometime in mid-day, their roof was on fire:

“We all ran outside, the kids and I were standing near the fence waiting for tor some things to be brought to us (my nieces failed to put their shoes on when running outside). So Illia went inside to get them, while both my mother and my sister came to stand beside us. Illia heard a bombardment aircraft flying overhead, and called out: ‘Girls, hide!’ And that was all I remembered…”

The shockwave destroyed both Illia’s unit and a neighboring house. The man rushed outside, to where he left the women standing and tried to find his wife — but she was nowhere to be found. Instead, he saw his mother-in-law Zhanna, who was on the edge of dying, and his own father, barely alive with shrapnel wounds.

When the smoke cleared, he saw Tetiana’s dead body under the rubble. Their youngest daughter, Varvara, was still alive, but the girl had suffered severe shrapnel wounds. Scooping up his daughter into his arms, Illia ran to the Police Academy where the Ukrainian military was stationed, yet they couldn’t open their door. There was a bomb shelter nearby, where the volunteers saw Illia with his bloodied daughter in his arms and let them in. They tried to give the girl the first responders’ aid, but the chances of the girl surviving without a doctor’s assistance were meager. Olena was also brought to that bomb shelter, and one of the people hiding there volunteered to drive them all to a hospital.

It took them quite a while: they went here and there, trying to find a doctor that could help Varvara. Finally, when they reached Hospital #3 and found that they, too, didn’t have a neurosurgeon, Varvara passed away in her father’s arms. On March 14, Tetiana and Varvara Plokhikh, and Zhanna Rostovska were gone.

When Olena Rostovska came to her senses the next morning, she had a memory loss. The woman spent two weeks, not knowing who she was, not even her name.

The woman spent several weeks, hospitalized for her concussion. While she was taken care of by the medical staff, her brother-in-law Illa and her niece Karina took care of her young daughter.

Evacuation from Mariupol

Illia was the first one to evacuate, taking both children to Krasnodar. Later, volunteers brought Olena there, too. When the woman was being driven through Mariupol, she shut her eyes, so she wouldn’t see the ruins of her beloved Kirovskiy city district. They were surrounded by ruined high-rises and one-family homes where the bodies of people whose lives were cut short might still remain.

At first, Olena was taken to the so-called “DPR”, and from there, she was on her way to Krasnodar. Olena says they were lucky to go through a filtration camp quite swiftly: it was lunchtime, and not that many people were waiting in line. So soon they were on their way again.

Illia Plokhikh and his daughter Karina were waiting for her in Krasnodar. The woman recalls that they had spent about two weeks in Krasnodar until she got better. From there, the family parted ways: in early April Illa took Karina to the Czech Republic, while Olena and her daughter first went to Georgia, and from there, they headed to Greece.

Today the family that had to endure so much together is split between the Czech Republic and Greece. The widower and his daughter do not want to talk about the death of their loved ones and try really hard to move on.

As for Olena, she dreams of returning to Mariupol, even despite the bombings, and give her relatives a proper reburial, getting a chance to bid farewells.

It was after her evacuation from Mariupol that the woman learned the location of her sister Tetiana’s, youngest nice Varvara’s, and her mother Zhanna’s graves were:

“Varvara was buried near Hospital #3, while my mother’s and sister’s grave was in the yard of the house where we were hiding, near the road. Illia spent four days digging that grave all on his own, with nobody there to help him. He then dragged the bodies and lowered them to their grave, and then covered them with soil. I do not know if I could keep myself together if I were around back then.”

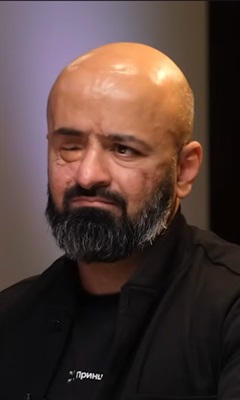

Olena Rostovska.

Olena Rostovska.

“I feel so empty, so devastated right now. My daughter is my only reason to live, to carry on. I feel so hollow now, with no emotions left inside me. From that very moment I woke up one morning after March 14, I never felt even a tiniest bit of joy. I feel so bad for my close ones having to die so young, for what happened to my city. Occasionally, a rush of emotion washes over me, and I feel like I’m losing my sanity. I lock myself in my room and spend hours and hours crying, not going outside,” says tearful Olena.

Olena’s sister, Tetiana, was killed a month shy of her birthday 3 she was supposed to turn 39 on April 14. The woman says that she used to pray to God that Mariupol was spared and that only a little blood was spilled.

“Maybe it’s the blood of my family and other residents of Mariupol that was shed to pay that price.”

A woman with her name in her pocket: the story of Natalia Kharakoz, a journalist and writer

Natalia Kharakoz.

Natalia Kharakoz.

Natalia Kharakoz, a journalist and writer, member of many professional artists’ associations, and head of Azovie Literary Club died in Mariupol on March 29. Her granddaughter Hanna Prokopenko spent a long time looking for her grandmother's burial place while staying in evacuation abroad. She agreed to share her story.

Before February 24, Hanna Prokopenko lived in Mariupol with her parents and her grandmother Natalia. The woman worked in media and wrote prose, and it was her late grandmother who influenced her choice of career.

“Natalia Kharakoz was a talented journalist and writer, member of many professional artists’ associations and head of a Literary Club, and overall stylish, sophisticated, and wise woman who inspired hundreds of people. She was an incredible optimist and a caring grandmother. My grandmother was my greatest influence, it is her I owe being who I am,” shares Hanna.

Hanna Prokopenko

Hanna Prokopenko

Hanna remembers her as a sensitive, wise person. For them, the generation gap was nothing. Natalia accepted her granddaughter’s opinions and decisions despite not understanding them. As a teacher, Natalia Kharakoz brought quite a few people into writing and journalism. She wrote her pieces in Russian and Greek and was a literary columnist in Pryazovskiy Robochiy (Ukr. for “Pryazovia Laborer”) where she published her literary reviews and the works of local writers. When her column was discontinued, the old lady took it to the Internet and became a blogger.

The family lived near Mariupol downtown. On March 1, a missile hit Hanna’s yard. Up to that day, only the suburbs had been shelled, so the woman immediately decided to evacuate. Back then, she only took with her a couple with a small child who lived nearby.

Her relatives, grandma included, refused to leave. Back then, the woman thought that their evacuation was hard, with all the shellings, vehicle and bodily searches, and all. Today, however, Hanna believes that they had it the easy way.

It was March 2 when the woman last spoke to her grandmother. The conversation was a short one, with the old lady saying she was fine. Later they kept tabs on one another through Natalia’s parents when they came to visit the elderly lady. By that point, their flat had no windows, so the grandmother lived at their neighbors’. And later, there was a total lack of contact.

“For quite a while, I was trying to comfort myself with the thought that she couldn’t call me due to her number being disabled. I paid her telephone bills over and over, thinking she might see the replenishment and call me. I was lying to myself, for by that time, no Ukrainian cellphone provider covered Mariupol,” shares Hanna.

Buried under her name due to a note found in her pocket

When she lost the means of contacting her grandmother, Hanna looked for her many relatives in search groups related to her apartment building. The main idea of those groups was that the people who migrated from one surviving building to another and later managed to escape the city shared information on remaining people and property.

Several times, the woman was assured that her grandmother was alive and hiding in a basement. Later, one of their neighbors informed Hanna that her grandmother had died, but offered no details. Upon that, Hanna’s parents managed to contact her neighbor, the Head of the homeowner’s board, who offered them some detail on how Natalia Kharakoz had died. However, even today the information is scarce.

The neighbors informed them that Natalia had died in a basement after yet another bombing, possibly from a cardiac arrest. At first, she was buried with some other neighbors in a mass grave, right in the yard of their high-rise. Sometime later, that grave was dug up, the bodies removed, and Natalia was reburied at Starokrymske cemetery, the only active cemetery in Mariupol.

According to Hanna Prokopenko, it took them quite a while to verify that information: had her grandmother really died, whether she had been buried, the location of her final resting place…

“I’m currently staying abroad, and it hits me hard that I can’t give her a proper burial, can’t appropriately bid my final farewells. I feel like doing something in her memory, like publishing her books. But as of today, I’m still pulling up my strength and resources, primarily my moral resource.”

As of today, Hanna is trying to gain access to Natalia Kharakoz’s blog, to honor her late grandmother and make sure that her cause lives on.

Thousand of lives lost for the sake of replacing Ukrainian address plates with those in Russian

Hanna Prokopenko is unsure whether she will return to Mariupol one day, and whether she wants to return at all. It takes time. Mariupol shill has problems with communication, with the only service provider working in the city at all being “Feniks” from the so-called “DPR”. But the city strives despite death. Today, entire neighborhoods are being razed, often with bodies of the dead Mariupol citizens still inside the buildings. Nobody really knows how many citizens died. In some neighborhoods, the tap water supply is back, but the quality of that water is terrible due to plenty of decaying bodies. The lines to grocery stores are huge, the surviving housing accommodations are scarce. The only thing the Russian army did truly achieve is that they replaced the Ukrainian address plates with those in Russian.