Hear the Voices of Ukrainian Journalists from the East. They Are an Outpost of Freedom of Speech Now

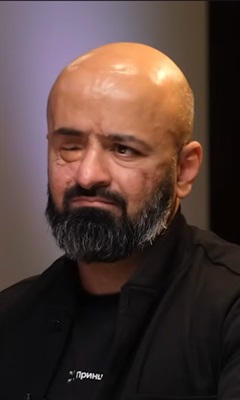

When we were invited to this event, I hesitated for a long time whose voice I should be today.

Perhaps, I should be the voice of my hometown — Bakhmut, in Donetsk region. For me, Russia’s war against Ukraine started in 2014, when for three months in a row the city shuddered from pro-Russian rallies, fake referendums, and propaganda. Working under occupation was a great challenge. My city remained under the control of Ukraine, but I lost my Donetsk then. Now the war continues for me — aerial bombs and missiles are being dropped on Bakhmut. Now I watch with horror as the cities of the East, on which we reported for four years in a row and in which we looked for the agents of change, where we talked about development and reforms, are being erased from the face of the earth. Mariupol. Volnovakha. Rubizhne. Popasna. Severodonetsk. Kramatorsk. We remain the voices of these Ukrainian cities crippled by Russian aggression.

Perhaps, I should be the voice of Katya, Maryna, Anya, Inesa. These are my colleagues, forcibly resettled women from Donetsk and Luhansk. They were building their new lives in Mariupol, Kharkiv, Severodonetsk, Kyiv. Due to the threat to their lives, they could not stay in the occupied cities, due to the threat to their lives — in the cities with active hostilities.

Katya’s fate hurt the most — for almost a month we had no contact with her in besieged Mariupol. Luckily, she managed to leave together with her one and a half year old son. All of them — Katya, Maryna, Inesa, Anya — are currently documenting the stories of those who have suffered from Russian aggression. Sometimes even I, the editor, find it difficult to read these stories without tears.

Perhaps, I should be Olena’s voice. Our colleague from a local media in Luhansk region in a city now occupied by Russia. A few weeks ago, we have got to know that members of the editorial staff had been arrested and are being held in the basements of the local pre-trial detention center. Under the threat of 15-years imprisonment or execution, they are required to cooperate with the occupation authorities. It is no longer possible for her to leave the city.

Perhaps, I should be the voice of Oleksandr Makhov. A television journalist from Luhansk. For the second time in eight years, he left his profession and went to the front as a volunteer. He soon planned to marry his fiancée. But on May 4, he died under shelling on the front line.

Perhaps, I should be the voice of Pavlo and Yaroslav. These are the editors of local websites in Popasna and Volnovakha. Quite a paradox — the cities were almost completely destroyed by artillery and aviation, but the evacuated teams still continue working — helping with their texts those who left and those who remained to survive this war.

All things considered, I want to emphasize the safety of journalists, who now continue to do their job in unprecedented conditions, facing great risks. We stand in solidarity with our colleagues who have been persecuted, tortured, attacked, and even killed. Russia must be stopped.

Now, in the conditions of war, we as media must be the voice of those crying out in pain. We want to remain an outpost of free people. An outpost of freedom of speech, which we took with us in our suitcases when we left our native cities and our native East. As long as we can, we will publish stories that will become a new history of Ukraine’s struggle for its freedom.