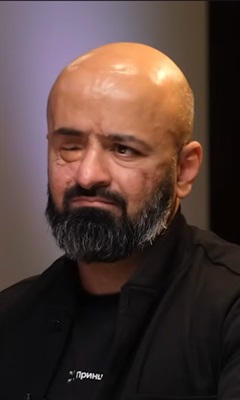

I’ve spent 40 days in a filtration camp in Bezimenne. I’ll never forgive Russia for what it’s done

A military man got on the bus and said that if something went wrong, he’d simply shoot us

Under bombing, getting coal in the city to heat the stove, in queues for water — thus we: my wife, our relatives, and me — survived until April 13th. It was the most ordinary day, I guess we even managed to go and get some water. Two men in Russian military uniforms came with machine guns. As we realized later, we were very lucky for they were quite courteous. Those who were taken away by other militaries said they were dragged out of their homes by hair, cursed, threatened. But we, as far as I remember, were even greeted.

One of them immediately went to inspect our home: he looked under the sofa, in the wardrobe, and so on. The second one started to make a list of all the people who were at home. He was especially interested in males. He wrote down their first and last names, phone numbers, registration. When the list was made and the house checked, they said that the males would come with them for two hours. I remember that clearly: two hours to get checked and talk there. According to them, this was supposed to be in Sartana. They took my wife’s dad and me, as well as all the males from the village. As it turned out later, 200 people were from Myrnyi alone. We got on the bus, there were already men on it. I was really lucky that I was in my running shoes — there were also men in rubbers on their bare feet or in flip flops. People went as they were when they were caught.

We were all taken to a facility which was positioned as a small headquarters. There were many males from Mariupol there. And we were again recorded, in a new list. We were for the first time examined: pockets, things, bodies. They checked if we had any tattoos. They believed that the Ukrainian military often made them. So such body examination was one of the identification methods. They didn’t find anything forbidden with us and sent us to the bus. There were about ten such buses.

We went to Sartana; they dropped us off near a broken House of Culture. It had neither windows nor doors. There, primary sorting was carried out: those to be sent for filtration were sorted from those to be sent somewhere else. We were divided into several groups and told to hand our documents and phones. They called us to a separate room one by one. The people sitting there had already studied the contents of our phones. Everything was checked: correspondence, pictures. They were looking for images of any Ukrainian symbols, everything they might dislike, even in no way related to the Ukrainian army and the ongoing war.

I returned to my bus and, as strange as it may sound, I was in a good mood. I thought I was leaving home for two hours. It was probably naive to think so, especially since a military man got on the bus and said that he didn’t know any of us and if something went wrong, he’d simply shoot us all. Nobody even thought to interfere. Somehow it seemed that he could do that.

They said that they’d send me to Donetsk for the final trial. I didn't realize what that meant

As it turned out, I prepared for filtration pretty badly. There was a lot of indignation in my correspondence about what was happening. And this indignation was quite emotional and, of course, related to Russia, Putin, and other things regarding the “Russian world.” Since they saw that, we couldn’t “get friends.” And it was impossible for me to leave or refuse to communicate.

While talks with others took about 15 minutes, I was kept for two hours. They asked me whether I consider them terrorists and why I disagree with them. My replies surprised them. I spoke quite emotionally and, of course, honestly about the war. They listened to me and asked more questions. Surely, my subsequent replies didn’t satisfy them. They laughed and joked a lot. It was very unpleasant. Then I was persistently asked to voice my opinion of Zelensky. They expected to hear something bad rather than what I told them for they obviously didn’t like him. At the end of our talk, they said that they’d send me to Donetsk for the final trial.

At the time, I didn’t realize what that meant. But I got afraid and I didn’t want to go to that threatening Donetsk. Still, they never sent me there; apparently, they didn’t find anything that bad. When they gave my passport back, I thought that I had passed filtration. But at that moment it hadn’t even started.

It was the very first selection to decide who and where would go further. Late in the evening we got back on the buses and sent further. Of course, we had no idea where. We drove long enough. And we realized that we were going further away from home, and no one knew how to get back. City entrances and exits were closed. There were many checkpoints, and I thought that when they let me go, I wouldn’t be able to pass that road even on foot. I got increasingly nervous.

An hour and a half later, we were brought to a school. As it turned out, we got to the village of Kozatske. As far as I understood, refugees used to be placed there since the school staff said that we were the first such ones. Which “such ones” and why we were the “first” they couldn’t explain: no one wanted to talk to us.

The school was quite equipped to stay there for a while. Throughout the school, in classrooms, corridors there were mattresses, jackets, or some kind of bedding on the floor, some rags to sleep on. We all settled somehow. Not all of us had blankets. Those who came in jackets could use them as blankets. Apparently, those amenities were to satisfy all our needs.

The military said that we would stay there and would be taken in turn to Bezimenne so that everyone could go through filtration. We realized that we would stay in that school for long. And then they would either take us back or just let us go. It was extremely foolish and naive to think so.

The first one asked: Where did you serve? I replied honestly: Nowhere. In response I heard: Don’t fucking lie to me!

I couldn’t understand what was happening and felt anxious. My wife’s father, me, and all the males from our street were placed in a separate classroom. We were taken in groups of several people to Bezimenne. For that filtration I had already prepared better. When I got my phone back, I started deleting everything from it. But then I realized that leaving it so obviously empty would be unwise for it could raise suspicions. So I deleted only the content which, in my opinion, could provoke questions from their side. I was thus sure that I prepared well.

I went to filtration in the third group. That’s how it was all like. At about 1 a.m. one of the military men came into the classroom and said that another group was being formed. Though everyone was asleep, I thought that we should go. My logic was something like this: it was nighttime and they were already quite tired. And they might be less careful. Perhaps it was indeed so. At that time, I was still trying to plan my path. I signed up for the trip. We got on the bus. It was raining heavily and it all seemed quite oppressive. Besides, all of us had no idea where we were going. Though we were told where we were being taken, we didn’t trust them. While there are 20–25 kilometers between Kozatske and Bezimenne, we drove for more than an hour. All the roads were destroyed. It was simply impossible to drive.

We arrived at a tent camp in Bezimenne. There were a lot of military men there. I’d rather say those were large tents. They were indeed large, 40 square meters each. And we were to visit two of them.

Five of us entered the first tent. I saw a table next to which naked males were sitting with bags on their heads and hands tied with tape. One of the militaries was asking a bound man with a bag over his head about something. I heard neither questions nor answers, but he beat him for every answer, strongly: on the back, on the head. The man was in pain.

We were stood against the wall and then separated again. Soldiers were sitting at the table in front of us. They were very aggressive. Their questions were standard. First: Where did you serve? I honestly replied: Nowhere. In response I heard: Don’t fucking lie to me. My replies to all subsequent questions evoked the same reaction. After a physical examination, they asked in detail who I was, where I came from, whether I knew anyone from the military, especially from the Azov battalion, police, rescuers, deputies, journalists, and so on and so forth. They were interested in anyone, wanted to get any information. It was so infinitely long that it seemed to me that the interrogation lasted for several hours. Still, later everyone said that each of us was given about 20 minutes.

As it turned out, not all the men who went in there with me managed to leave. Some were taken elsewhere. They were tied up. The militaries put on bags on them and took them somewhere. I’d been surprisingly lucky and after the first tent I was taken to the second one. There were a lot of computers, some devices in there. It seemed to me that those were some kind of stations. I don’t know what they were for. The equipment looked quite unusual. There were a lot of tables with many military men sitting at them. Before that, I’d only seen militaries in the so-called DPR uniform, but there it got clear that there were Russian militaries with their identification marks on their uniforms.

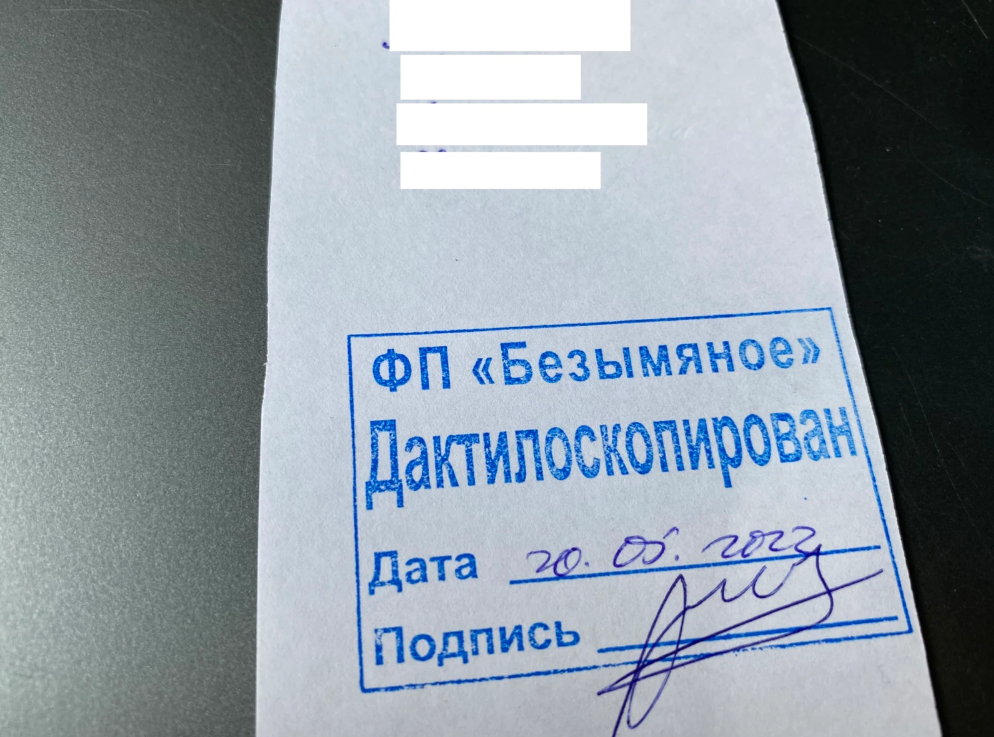

We had to come up to each of the tables and fulfill the requirements. The first table assumed collection of fingerprints. Moreover, they collected not only fingerprints, but also palmprints, handprints from all sides: front, sides. If I remember correctly, they took palmprints including all fingers and then a separate impression of each. I remember I was also taken a fingerprint, just one, when I got a passport. And there, in that tent, handprints were taken almost up to the elbow.

After that, I was ordered to come up to other tables. There I was again asked questions and told stories about myself, where I served, who I worked for, what education I had, where I was registered and where I lived, what I thought of the actions of Mariupol mayor, whether I had any relatives in Russia, Ukraine, abroad, whether I knew any military men personally, and what I thought about the special operation, the policy of Russia, Ukraine. All the questions had to be answered correctly. If you answered incorrectly, then the chance to go to the same place where the beaten men with bags on their heads had gone skyrocketed.

Фото: Photo credit: Sever.Real

Фото: Photo credit: Sever.Real

The examination process was long and humiliating, but I passed filtration. I was given a small piece of paper with the date and my name handwritten on it. It was stamped “fingerprinted” and stated the procedure’s address. In my case, that was Bezimenne settlement. They told me that using that paper I could move throughout the territory of the so-called DPR. Of course, it was they who needed that piece of paper, not me, but I was also to somehow benefit from it.

With that paper, I got on the bus. It was already early in the morning. Like everyone else, I thought everything would be finally fine. But since we weren’t allowed to go home yet, it was obvious that we were waiting for everyone else to pass filtration. Why do I say that I thought so? Because all of our questions remained unanswered. At best, they ignored our words; at worst, they, so to speak, swore. They demanded that we not at any rate approach them. And when everyone was finally filtered, they still didn’t let us go home. For the first two weeks, I waited desperately, and then I suddenly realized that would continue indefinitely. I realized that I shouldn’t wait but try to build my life in those conditions.

We were fed twice a day, but sometimes it seemed that it would have been better to go without it. The food was simply disgusting and it was impossible to eat it. But we had to choke on what was given because there were no other options. There were only two cooking ingredients: pasta and rice. Pasta was cooked into some kind of a wallpaper paste. I could only guess that it was pasta because I could rarely find its parts in that mash. Herewith, it tasted like the most tasteless soup that you can’t even imagine. Besides, the food wasn’t salted. By the way, in the first week we were also given bread.

Over time, the school started to run out of even the food we had. Therefore, they made announcements in the village asking residents to bring food to school for us. And, as I later understood, the village fed us. Several times the men from our camp brought food to the school. But in general, everything that the locals brought had never reached us. The men said there was stew and a lot of canned food. Well, they once gave us some honey bread. And a couple of times they indulged us in soup.

I don't know if we had lice, but we were all itching

Probably, during the war my needs reduced so much that though the conditions in which I stayed seemed awful, they still aligned with the situation in which I found myself. And my mind didn’t ask for more. There were sinks in the school and using this only source of water we had to bathe and perform all hygiene procedures. We could use the school toilet outdoors. And, of course, this concrete structure was awfully dirty. They gave out one square of single-layer toilet paper, about 10 by 10 centimeters, per day. I don’t know how they imagined that. However, those were the conditions there.

Someone was always sick. Infections were quite common there and they were caused by the bad water that we drank just from the tap. Perhaps that is why they started to get water tanks to the school. We could fill barrels with it. I don’t know where they brought that water from, but it was good. Probably we all got sick eventually, including me — though in a lighter form. Apparently, at some point, an outbreak of coronavirus started in the camp. Some had obvious pneumonia. Some had severe stomachache.

Відео із середини фільтраційного табору селі Безім'яне — 2 частина pic.twitter.com/j11rXOxpit

— hromadske (@HromadskeUA) May 5, 2022

Naturally, none of our guards were particularly bothered. On the first floor of the school there was a woman who dispensed medicines upon request. That could be, for example, paracetamol. Seriously ill people were then taken by an ambulance. They seemed to be taken to Novoazovsk or Donetsk.

Over time, skin diseases started to accompany infectious ones. I don't know if we had lice, I guess we did, because we were all itching. There were no sanitary conditions. For a very long time we had no soap, shampoo, or powder.

People tried to save the man, but he died. The body lay in the corridor for a long time

On the very first day, a man died. A young guy was the only one who tried to save him. The man had two seizures. The first one was in the morning. That guy was nearby and managed to help. It looked like an epileptic seizure. And in the evening I heard the sound of a body falling on the floor. The man hit hard when he fell. He was bleeding from his nose and mouth. It was obvious that everything was bad. The guy who saved him in the morning told the military to call an ambulance or at least a paramedic. But they ignored him. The guy carried out resuscitation and performed a cardiac massage for 20 minutes. And those militaries were just standing nearby and watching. They didn’t really care about what was happening. The man died. The corpse lay in the corridor for a long time, then someone asked to cover it, and he was allowed to take a sheet. Later we were told to take the body to the school gym. And there it stayed for maybe another couple of weeks. I’m not sure.

Публікуємо відео із середини фільтраційного табору селі Безім'яне — третя частина pic.twitter.com/vfKZS43S0J

— hromadske (@HromadskeUA) May 5, 2022

One of the men who stayed with us at school kept persuading them to let him go. He lived with a paralyzed mother. Of course, there was nobody to look after her while he was there. Nobody let him go. And after some time he got to know that his mother died. Perhaps even due to hunger. He asked them to let him go at least to the funeral, but they didn’t.

There was no schedule. We were completely free, just on a guarded territory. We could walk around the school, we could lie down on our so-called beds. No one called for breakfast or lunch either. Our guards didn't care what each of us was doing. Not to confuse the days, we wrote dates on the blackboard.

Reading Ukrainian news could be severely punished

To be honest, I can’t say I hated them. I’d rather say I couldn’t understand that, absolutely. I didn’t understand what was going on. And I was concerned rather with lack of understanding of what was happening than with anger towards someone. It was all surreal — a hell of incomprehension. And I just wanted that to end as soon as possible.

My colleague, having learned that I was in Kozatske, intentionally stopped by to give me 15,000 rubles when leaving Mariupol. It was a huge amount, and thanks to that I could get a phone. There is a mobile network Phoenix in the DPR. To get its SIM card, you had to try very hard. It was sold only at the post office and only for rubles.

It was another problem, because no one had rubles. The second problem was that when purchasing that SIM card, you had to provide all your original documents and their copies. Of course, you could buy only one SIM card. It took me two weeks to become the owner of the coveted SIM card. But when I bought it, I had very good feelings. I’d never had such difficulties to find a connection before. And when I got it, everything got much easier.

I had no connection with my wife and mother until then. After that, with the help of carriers, I sent a SIM card to Mariupol. This service cost 100 hryvnias. And then I could call my wife and mother from a friend’s phone. In cases like with the SIM card, I felt relieved that I was able to do that. It was still very hard to joy there. In those conditions, there was simply no joy.

Surprisingly, at nights there was Internet at school. The connection was very poor, but it enabled us to find out what was really going on in Ukraine. Reading Ukrainian news could be severely punished. So it had to be done very carefully.

Over time, we started to settle down. Everyone had something of value. It could be, for example, an immersion heater or tea

Our conditions there were getting more “comfortable.” If in the first week we had to sign up with our security guards to leave the school building, later everything’s got easier. They, apparently, were also tired of everything, they abandoned the lists, and we started to go out freely. That was my only freedom.

Relationships were generally good. But there were occasional conflicts. That was clear since everyone was tired, stressed, angry. I wouldn’t say those were serious conflicts, no, just the most common, daily ones. Over time, we started to settle down. Everyone has something of value. For example, an immersion heater. And if someone took it and didn’t give it back for long, a rather serious quarrel could occur about that. There were even several fights. Each was for some valuable household item: soap, tea, powder. Given the conditions, this wasn’t surprising.

I hardly talked to anyone and spent most of my time alone. A man changes greatly. Frankly speaking, even before that, the village of Myrne wasn’t that good, but in those conditions people got even worse. Over time, men learned to get alcohol to the school. And after they got access to it, their behavior even worsened. Thus 40 days passed.

In Narva, I looked at a calm measured life. I got afraid events similar to those in Mariupol could happen there

Exactly on the 40th day we got our documents back but still were explained nothing. We were among the first to go to Mariupol by a passing car. We drove into the city from the Vostochny microdistrict, and then for the first time I saw how badly the city was destroyed. So I had new impressions. Though I already had immunity to what was happening, it was painful. When we got there, we were treated to a delicious lunch. If everything is fine in your life, wheat porridge with tomato doesn’t sound very tasty. But when you spend 40 days in Kozatske, it means three Michelin stars for you. I took my wife and on the next day we were on our way.

To get to Estonia, we had to go through Crimea to Russia. There was another thing: I still have a Donetsk residence permit though I was born and grew up in Mariupol. In 2013, I entered Donetsk University. Since 2014, I haven’t been in the city, but I’m still registered in the university dormitory. And this fact scared me greatly, because I didn’t want anyone to think that I was somehow related to the DPR.

Those were already standard questions for me and, apparently, I provided quite convincing replies. But two men from our bus were forced to squat in military body armor 100 times. That was kind of entertainment there.

The checkpoint in Ivan-gorod was completely different. If in Chongar they only swore and cursed, in Ivan-gorod I for the first time was addressed politely by a person in Russian uniform. However, there too Russia remained true to itself: again fingerprints, paperwork, photographing, questions. It was just another filtration.

But in Estonia, when we had just crossed the border, people asked how they could help. We were immediately supported, support was felt just everywhere. Ukrainian flags are all around here. And there are such people here who we’ve been longing to see.

When we were in Narva, I looked at a calm, measured life, and at some point I got afraid events similar to those in Mariupol could happen there. Estonia also borders with the Russian Federation and, as we understand now, no one is immune from war.

Now we are starting to live again. I don’t yet know what has changed in me in the long run, but I feel the changes are significant. First of all, I’ll never take up arms. Especially to hurt someone. I’ll never refuse to help people who need that. And I’ll never forgive Russia for what it’s done.