Black skies, black hands, black water: from Mariupol to Finland, through a Russian filtration camp

In her interview with Evacuation.City, the woman spoke about her family surviving the blockade of their home city and ultimately reaching Joensuu, Finland.

The Early Days of War

To Viktoria, her recollections of their life in February are a blur, with individual dates being blended into soot-soaked kaleidoscope in her head.

“I recall March 2, when Mariupol went into blackout. First the electricity was gone, then the natural gas supplies, and then the rest of utilities. During those first weeks we were shocked by the fact that there was no evacuation. We saw our city falling apart before our very eyes, yet we had nowhere to run. There were no preparations for the war, nobody stockpiled food and all. That spring had been a cold one,” the woman recounts.

Just several blocks away from Livoberezhniy [Ukr. “Left Bank”, — translator’s note] district where the makeup artist resided, the unknown was spread out: nobody could tell whether Viktoria’s coworkers and friends, people with whom she had been in touch a mere week before were, were still alive and well.

Since mid-March, the Nosulenkos’ life had been a one long groundhog day. Every morning started with a quest, where to get some relatively clean water and some firewood.

Mariupol, Livoberezhniy district.

Mariupol, Livoberezhniy district.

“We had to cook on open fires. As for water, there were several unreliable ways to obtain it, which included melting snow. The snow was dirty, because gunpowder and soot from the shelling was everywhere: on our faces, on our hands, on our underwear. Even the skies turned black from the never ending smog — despite the factories were no longer in operation. There was one single wellhole in our whole district that still operated due to being solar-powered, which meant there was no water when it was overcast or the sun was down… but the lines to that wellhole were huge, you had to be there at 4 a.m., and it wasn’t for granted that you would end up with a bucket of water by 8 p.m.,” says Victoria.

It was the rain which was considered a bigger luck, giving the Mariupol citizens an opportunity to save up some rain water. It was as black as everything around them, but at least that water was freely available. The air was soaked with that burning smell, scraping your lungs from the inside.

“Azovstal had been shelled 24/7. That loud gnashing sound of metal breaking is something I can’t ever forget. That was something you heard both at night and at dawn, like, 4 to 5 a.m. The Russians were fond of shelling the city at dawn break, and there went your sleep. We were afraid to light candles, as the light might give away our location, so we lived in total darkness as much as possible. When they [the Russians, — translator’s note] were shelling our suburban neighborhood, we didn’t get to sleep at all,” recalls Viktoria.

Azovstal was bombed day and night.

Azovstal was bombed day and night.

At first, the Nosulenkos stayed at their home, seeking shelter in the family’s cold, damp cellar. Over time, the whole family got ill, and due to never ending cold, they all got some strange form of allergic reaction. Sleeping in that cellar was unbearable, so ultimately they stopped rushing down to the cellar altogether, leaving it all up to fate. In early April, the frontline shifted a bit, and so did the line of shelling. The Russians started destroying Azovstal with even more intensity, but at least Viktoria’s neighborhood had some respite. Soot was permanently in the skin of each member of the family: there wasn’t enough water even for cooking, not to mention the possibility to wash themselves or their clothes.

On April 15, in mid-spring, it was snowing heavily in Mariupol. It was then that the family learned about the opportunity to leave the city, but only through the Russian filtration camps and then the enemy’s realm. In order to pass the Russian roadblocks and get to the free Ukrainian territory, one had to pay a hefty sum, EUR 1,500 (UAH 44,000), the money that the family didn’t have. Besides, every enemy soldier on their way there would expect additional personal bribes from evacuees from Mariupol.

It was late April when the Nosulenkos finally ventured to leave, even if it meant going through a filtration camp. Viktoria is an orphan, so it was only her in-laws that they left behind.

A district in Mariupol.

A district in Mariupol.

“My mother-in-law was 70, she refused to leave and start from scratch elsewhere. In her windows, there are several sacred icons in every window sill. That’s her protection against the dangers of war. A house next door, literally 4–5 meters [13–16 feet, — translator’s note] from her home, had been hit directly by a projectile. It was the stone fence that saved me mother-in-law [from the shreds and the debris, — translator’s note]. Those people whose fences were made of sheet metal saw mortar fragments cutting through that metal like it was butter. She has some chickens and a shepherd dog at her home. We tried to convince her to leave, but she was having none of it. All we can do now is hope for the best,” recalls Viktoria.

The Nosulenkos left the city in their family vehicle. It was a miracle that the vehicle survived, given that each day some car or other exploded both in the streets and inside garages due to shelling impacts. The whole new municipal transportation pool had burned to ashes, be it busses or trams (streetcars). So the family decided not to wait any longer and evacuate while they still had their vehicle.

Evacuation

To their utter surprise, the filtration went quite smoothly, as a family of a disabled child was rather quickly redirected to a shorter line, and because of their child, the father of the family was neither tortured by twisting his arms, nor threatened by putting a barrel of a machine gun to his temple.

Finland

After Pskov, the Nosulenkos went to St. Petersburg, which in near the Finnish border. They chose Finland because it was the nearest European country they could escape Russia to.

The Finnish boarder guards were as amiable as they could be. The evacuees from Mariupol were asked to tell their story, and then given accommodation in a near- border town of Konansua, in the premises of a former prison, while their temporary protection documents were processed. The prison was quite comfortable, with good living conditions and two hot meals a day. Besides, they were allowed to take their supper to their room. It was there where the family had spent their initial six days in Finland, and after that, an officer from the Red Cross gave them the key to an apartment in city of Joensuu. The family was told that they could spend up to one year in that apartment, and share that accommodation with another resettled family.

The Nosulenkos were open about how much money they managed to bring from Mariupol, so at first, they weren’t offered financial aid. When their ran out of savings, the three of them were offered EUR 350 (UAH 10,300). Finland doesn’t have any fixed rates that they pay to every resettled person, that sum is calculated for each family individually.

They were used to living by the sea, but it took them some time to adapt to the colder sea in Finland.

They were used to living by the sea, but it took them some time to adapt to the colder sea in Finland.

The caption on this photo reads, “HEI means ‘Hello’ in Finnish. Went to the waterside today.”

“At first, we received a grocery bag every two weeks. There are centers where you can get some second-hand furniture and household appliances when they have it available, and apply for some pots and pans. Our apartment was outfitted by the Red Cross, they even got us even the cleaning products and personal hygiene items. The Finns are very decent and people. They do not owe us anything, yet they choose to help us. The most important thing is that our people don’t abuse their kindness,” shares Viktoria.

Emotional Condition

A week prior to them leaving Mariupol for good, Viktoria and her husband opted to take a one last walk in their city district, despite the danger.

“There were corpses, that had been laying there for a long time. They were black and broken, scattered like dolls. We weren’t even spooked by those corpses any longer, as we had been during those first days or weeks. People who left in mid-March, they were stuck in that phase of panic and horror, stuck in that reality. As for us, we made a transition to a different reality, where you just carry on, regardless. Where you’d witnessed death and houses on fire, and couldn’t do anything about it. That’s why we have a different approach to appreciating things. When we cane to Finland, they told us, ‘You can stay, if you like it in here. We can help you find your first jobs if you like. Or, if you don’t, we can research some other options for you,’ and you appreciate that,” explains Viktoria.

A street in Mariupol.

A street in Mariupol.

While we were talking, the Nosulenkos’ cat kept coming into the room and going away. A calm and proud creature, that Mariupol sphinx survived the two-month blockade, yet still voiced his irritation every time he was locked out of the room. His psyche turned out more able to adapt to everything that transpired than the psyche of his humans.

Viktoria spent her early days in Joensuu in tears. While the family had tried to hold on while in blockade Mariupol, the woman just broke down, unleashing everything she had been suppressing in the city ruined by the Russians, as soon as they got to safety.

“I was crying profusely, uncontrollably, wailing and stuttering like a child. You do not cry in a warzone, you are too busy surviving, and if you aren’t, your family and yourself are doomed. Therefore, everything we went through caught up with us later, in safety. The farther from home, the more bitter it gets. It’s ‘like your skin has been ripped off you’ sort of sensitivity,” explains Viktoria.

Once in a while, the Nosulenkos are able to get through to one Viktoria’s in-laws phones. Their conversations are short: “How are you?” — “Alive” — “Thank God!”. Mostly, that’s all that the cellular connection allows them in terms of communication.

Adaptation

Joensuu has little to none high-rises, and each city district is separated by a strip of forest. Despite the Finnish climate being quite cold, the Nosulenkos have adapted over time. The Finns do their best to help Ukrainians through pre-existing social programs for vulnerable social groups. Several days a week, people can get free grocery bags at specialized centers. However, one has to be there early, for the number of those bags is limited.

“The Finns wonder why the Ukrainians keep taking so much food. Like, they’ll give you some more tomorrow, why grab so much? While many people, us included, had spent several month not seeing a loaf of bread, so people tend take 2–3 loafs. The Finns don’t say anything, but they can’t understand it. I would like to take the opportunity and ask my compatriots to use up the aid they receive, or bring back those thing that didn’t fit. Don’t throw anything from those charity bags away. It hurts the Finns when they see their humanitarian aid in dumpsters. This is not hypocrisy, they really care about reusing and recycling things,” says Viktoria.

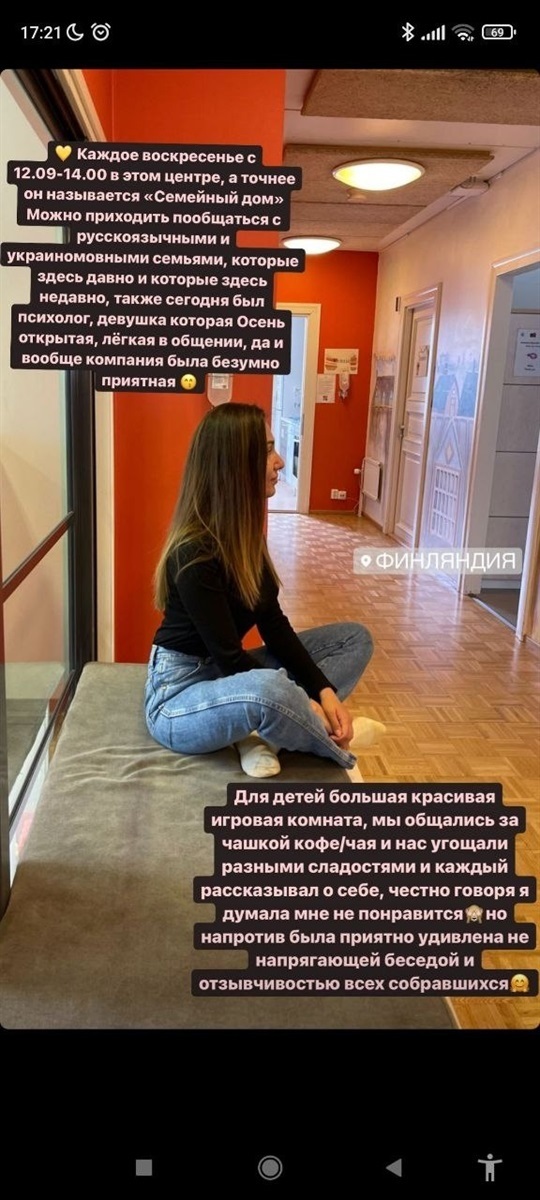

From time to time, Viktoria attends meetings with other Ukrainians.

From time to time, Viktoria attends meetings with other Ukrainians.

The caption on this photo reads, “Every Sunday, 12:09a.m. — 2 p.m., this Center (Which is called “A Family House” hosts meetings for Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking families, bot the newcomers and those who came here long ago. Today, there was a Psychologist in attendance, a very open and easy-going person, and the overall companionship was great”, “The facility has a large and beautiful game room for kids. We were talking over a cup of coffee/tea, and were treated to different sweets. Everyone told a bit about themselves. Frankly speaking, I was afraid I wouldn’t like it in there, but on the contrary, I was pleasantly surprised how at ease I felt during that conversation, and how generous and responsive the people in the gathering were.”

Job Hunt

While Viktoria’s husband want’s to try his luck in construction and seasonal berry picking, the woman is trying hard to revive her career in beauty services. She is already signed up by a modeling school, and has worked as a make-up artist at several photoshoots. Their child went to a local school and is assisted by a professional working with children who have ASD. Viktoria takes free Finnish classes, although the language doesn’t come easy to her (the Finns have their own words even for the terms of foreign origin).

Her stories on social media feature pictures from her projects, and Mariupol’s lost persons and lost-and-found animals posters, intermittently. “Troyitska Str., Mytropolytska Str., animals found, searching for owners”, or, “Missing person! Liuda, Tania, Myroslava, last seen in March, April, February…” People continue looking for their close ones, continue living.

“Yes, everything is broken and lay in ruins. You can succumb to depression and cry for a very, very long time, however, you still have to resurface and begin your life from scratch. You have to keep on living,” shares the woman.