I was in the blockade in Mariupol for a month. We fished to survive, and women baked bread

Russia has been blocking the port for 8 years

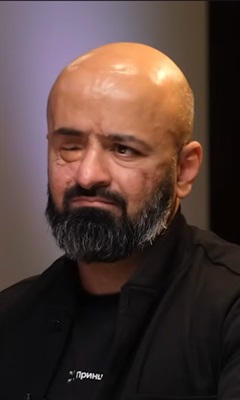

Vladyslav Myroshnychenko has been working in the Mariupol port since 2013. He first headed the sector of land management within the department of property relations. For five years, he was a member of the local city council where he defended the interests of his colleagues. Having resigned, Vladyslav took up a post at the trade union committee. He first landed a job as an advisor and then became head of the committee.

"The personnel of the Mariupol port has always been a close-knit team that held family traditions in high regard. Entire dynasties worked there. Each and every employee was valued and we were ready to help our colleagues out in any situation".

Once it was a port with the largest capacities on the coast of the Sea of Azov. However, Russia’s military operations in the East in 2014 had a bearing on the port’s cargo handling.

"In the past, 90% of cargoes used to be transferred from the Donetsk or Luhansk region. Since 2015, the volume of cargo has dwindled by 50%. Nevertheless, this has not discouraged port workers. Quite the reverse, it has given them an incentive to develop. In 2015, a decision was made to project a totally new and the largest agro-industrial terminal in the Sea of Azov and to start the construction works. The terminal was almost ready to be exploited".

Vladyslav Myroshnychenko on the premises of the port.

Vladyslav Myroshnychenko on the premises of the port.

An attempt was made to cut down on gas consumption as much as possible. A helium system came in handy for this purpose.

"Despite the implementation of modern technologies, the port’s operations were heavily impacted by the construction of the Kerch bridge as well as full inspections of ships close to Kerch-Yenikale canal. The arrival of all ships that were bound for the port would be delayed for days or even weeks".

"Before, port workers could not cope with loading ships. Ships would even line up waiting. However, Russia’s aggression effectively blocked full-fledged work of the port," says Vladyslav.

Despite external calamities, the atmosphere inside the team remained healthy as ever.

"People would spend vacations in our recreation centers. We would offer package tours and children spend their summer in the best camp‚ Young Seaman".

On the whole, the port functioned and developed. Having lost its usual volume of work, nobody gave up. As Vladyslav puts it, during a protracted crisis none of the employees were made redundant. The team was held together.

"The Mariupol port has learned to live in a new reality. Nonetheless, we refused to believe that Russia would stab us in the back with such ferocity until the very last moment".

A canteen employee said she had a premonition something bad would happen, which is why she had purchased a lot of food

Although nobody believed in a full-scale invasion, the Mariupol port became the only enterprise in the city that came prepared for it. Vladyslav says that the city’s mayor, Vadym Boychenko, did not take care of local citizens.

"He left everyone in the lurch. He left Mariupol on February 25. During the following 10 days, he published his videos but effectively did nothing for the city residents. He let his deputy, Mykhail Kohut, stay in Mariupol. Kohut convened meetings in which the director of the port, Ihor Barsky, invariably participated. They together were searching for ways to rescue the locals".

When hostilities in Mariupol broke out, Vladyslav and several of his colleagues with their families moved to the port. They lived there, cooked meals for themselves and for those who needed food as well as took shelter from shelling.

"We had food reserves and fuel, as well as generators. After all city communications were out of service, we were able to provide the locals and the military with food and bread. We delivered diesel fuel to hospitals that the port was managing. This lasted until mid-April before the port’s premises were occupied".

It so happened that two weeks before the invasion the management of the port had purchased food for its employees working on ships. It had been common practice before the war and this coincidence was quite fortuitous. A canteen employee said she had a premonition something bad would happen, which is why she had purchased a lot of food.

"First of all, we delivered food to citizens of the Prymorskyi district as well as to the military that was stationed on the port’s premises. Bread, water, and fuel were the most valuable things at that time. Our women would bake bread nearly around the clock".

Vladyslav says that his colleagues did truly heroic deeds.

"A colleague of mine worked 20 straight hours to load concrete blocks onto dump trucks that would then deliver those blocks to the main city’s streets. This was done in order to hinder the advance of Russian troops. He then went on to deliver these blocks on a KAMAZ truck himself. Under shelling, employees of the department for material and technical provision would open gas stations that were located in the cargo area".

Vladyslav with one of his colleagues.

Vladyslav with one of his colleagues.

In March, his colleagues and he managed to take the employment history books of the employees out of the port. They hid them on the only Ukrainian icebreaker ‘Captain Belousov‘. Those who managed to reach the port came to collect their own book.

At first, the premises of the Mariupol port hosted about 250 people. However, when shelling gathered pace, some were trying to get out of there.

"I took people out of the port in my own car and drove them to a checkpoint. From there they walked on foot. I would make several such trips a day. Until March 20, we had managed to evacuate almost all women and children".

Vladyslav lived with those who stayed at the port on a floating crane ‘Neptune 4’. There were 43 of them, including 8 children and 11 women. These were not only his colleagues but also their family members, since they believed that the port would withstand the Russian onslaught and that the Ukrainian army would drive the occupants out.

In April, they ran out of food stocks. To sustain themselves, the port’s employees resorted to fishing. They fried fish and cooked ukha (a popular type of clear fish soup in Ukraine — translator’s note).

Fish for lunch.

Fish for lunch.

"We had a bit of groats and sunflower oil. On the weekends, we would cook soup or borsch, which was a great delicacy. At first, when we still had some chicken, we would put everything into chicken broth. We used to give meat only to kids".

We held the port to the last

The management of the port in Mariupol remained on its premises until March 21. Vladyslav Myroshnychenko left it in April. He stayed there because he was afraid for his people.

He admits that his major worry was losing connection. He did not know what was happening in the city or what happened to his friends or his nearest and dearest.

Vladyslav remembers seeing Russian tanks popping up at the dock of the port out of nowhere. They entered the premises through the fourth gate of the port.

"At 9 am, our defenders were still there and then after an hour, Russian occupants came. Fierce hostilities ensued for several days. We saw them shelling the management building from the port’s premises. They were also trying to push our soldiers back. It was horrible, pillars of dust, destruction, explosions with dead bodies or torn limbs lying around. I saw dogs dragging torn limbs back and forth".

Once Vladyslav tried to escape from the port when a Russian tank went for him. He thought he would be squashed right in his car, but he managed to make a U-turn at the last minute, having only damaged his car.

Consequences of an ‚encounter’ with a Russian tank.

Consequences of an ‚encounter’ with a Russian tank.

When the port was captured by the Russian military, Vladyslav managed to flee. He says he was put up by a colleague of his who lived on the coast. He decided to leave at the earliest opportunity. He spent 10 days reaching Ukraine.

"I first found myself on a sandspit. There I was waiting for a humanitarian corridor. On my way to Zaporizhzhia, I spent three nights in a field. I then reached Dnipro and now I am in Kyiv".

At the moment, Vladyslav is recuperating, planning to carry on helping the military.

In May, the Mariupol port laid off its staff, having fulfilled all of its financial obligations.

"Our staff members are dispersed throughout the world now. Many of them have emigrated. Some have stayed in Ukraine. To the best of my knowledge, out of 3000 staff members, 400 have stayed in Mariupol. I am neither justifying their actions nor condemning them. Each of them has their own story. However, I find it quite sad to learn that my ex-colleagues begin working at the occupied port".