I spent 100 days in the Olenivka colony “Pit.” Counted days in prison using a tea pack

Anna Vorosheva told Svoi about her stay in the colony and her acquaintance with Yulia Paevska (paramedic Taira) in the Donetsk detention center.

I Have to Go Back to Mariupol, People Are Waiting There

In Mariupol, I had my own business in holiday services, which I started back in 1998. On the first day of the full-scale invasion, I let the employees go home, closed the storage and joined the volunteer hub Halabuda and the medical storage unit. It was there that I saw Taira for the first time.

On March 15, I met a woman I knew; her car was damaged and not running, without glass. She couldn’t start it. Together with other volunteers I towed her car to a garage on the outskirts of Mariupol.

Anna before the war

Anna before the war

With the start of the war Anna joined the volunteer hub Halabuda

With the start of the war Anna joined the volunteer hub Halabuda

We rode bicycles to the car market, it was already destroyed, and found the windshield under shelling. We attached it with mounting foam. Repairs were made using candlelight in the garage. At dawn, I came back to Halabuda, worked my last day, and handed over. And then I found out that there was a car, a jeep with manual transmission, and a female driver was needed.

On March 18, local volunteer Oleksiy Marchenko drove the car with the windshield fixed with mounting foam and I drove the jeep. There were seven other women with me. Oleksiy took us through the fields, bypassing the checkpoints, to the highway, and six hours later we got to Zaporizhzhia.

Field kitchen in Halabuda

Field kitchen in Halabuda

But I wasn’t going to stay there for long. I had to go to Mariupol to evacuate people, including women with children. My mother was also in Mariupol.

I took all my money, including credit money, that is 130 thousand hryvnias, but it was still not enough to buy a minibus. I then turned to BBC journalists, they made a post on Twitter that I was collecting money for the purchase of transport. In a matter of days, we managed to collect the necessary amount. Caring people helped, including Ukrainians who have been living in the Netherlands, the US, Canada, and Australia for a long time.

The plan was as follows: to load cars with humanitarian aid, take it to Mariupol, and evacuate people from there, including my mother. When I was in Zaporizhzhia, I remember my friend Alyona calling me from the Netherlands and saying that she was going to buy [me] a plane ticket to Eindhoven. But I felt I had to help people waiting for my help. If I didn’t go back to Mariupol, I would never forgive myself!

Without Further Ado, I Was Detained and the Car Was Taken Away

On March 24, I learned that my mother managed to leave Mariupol. But I felt I should help people waiting for my help. If I didn’t go back to Mariupol, I would never forgive myself!

In the evening of the next day, a convoy of three cars — a jeep and minibuses — with humanitarian aid left for Mariupol. On the next day, we were thoroughly examined and questioned at the checkpoint in Nikolsky. But then they let us go. We left food in the church in the suburbs of Mariupol, there were already more than fifty people there. And we went further to deliver food and medicines to the bomb shelters and to take people away from there.

We also had to get to one of Mariupol districts, which could only be reached through Melekine. We were detained in this resort village. The jeep was loaded with food, medicines, and fuel. We needed to get to the other edge of Mariupol, so we went through Melekine. And suddenly we were detained at a checkpoint near Mangush. The jeep had no documents, was full of groceries and gasoline. Without further ado, people with machine guns started to unload the jeep and, to justify their looting and “taking away” the jeep, they sent me and the driver to the police station in Mangush for filtration.

Now I understand that at that time they detained all people who voluntarily, despite the danger, strived to take the civilian population out of the war zone, especially the elderly, children, and pregnant women. At the checkpoint, I told them that I was going to take people to Zaporizhzhia to the territory controlled by Ukraine. I suppose this was the major reason for my detention and arrest. The armed military said that we were evacuating for money. No one believed us that we actually help people for free, from the bottom of our hearts.

On March 29, we were transported to occupied Dokuchaevsk, to the local district department. I would later find out that my driver had been freed while everything had just started for me. After Dokuchaevsk, I was brought to Donetsk on March 30, first, to the Department for Combating Organized Crime. There I realized I faced a threat of a long-term captivity. That’s when I got really scared. But I still managed to call my daughter and tell her what had happened to me.

On the next day, together with other detainees I was taken out of the building and put in a minibus without seats. We were sitting on the bus floor. They brought us to some gray building with huge metal gates and a separate entrance. Having entered this door, we found ourselves in the middle of a huge yard, where angry dogs were running to the right and left behind the metal nets. In that building, we, women, were examined, checked, and undressed. Many things were never returned to us after these examinations.

I Was with Taira in the Isolation Cell. There Were Five of Us and Three Beds

It was the territory of the temporary detention center. After the examination, the escort took me to an 18 m² cell. There were already three women in there. I realized they might have concerns about who I really was. And then I saw a familiar face. It was a woman who came many times to get medicines from the volunteer storage unit where I worked until March 16.

It’s just that she was exhausted, but her eyes and smile remained the same. It was Taira.

In the cell, we got to know each other personally. From the start, Yulia Paevska looks a strong, stable personality. From Taira I learned how she was captured, how she made her terrible way to this cell. She told her story, told about the children she took out of the hospital, the deaths of her brothers-in-arms, as well as the beatings and illegal demands made on her.

She also told me about all the peculiarities of staying in the detention center: when and what food they gave, what personal things I needed, etc. The worst part was that we couldn’t go out into the fresh air and open space, as well as lack of a shower. These details, supplemented by my personal observations, built a picture of dead ends.

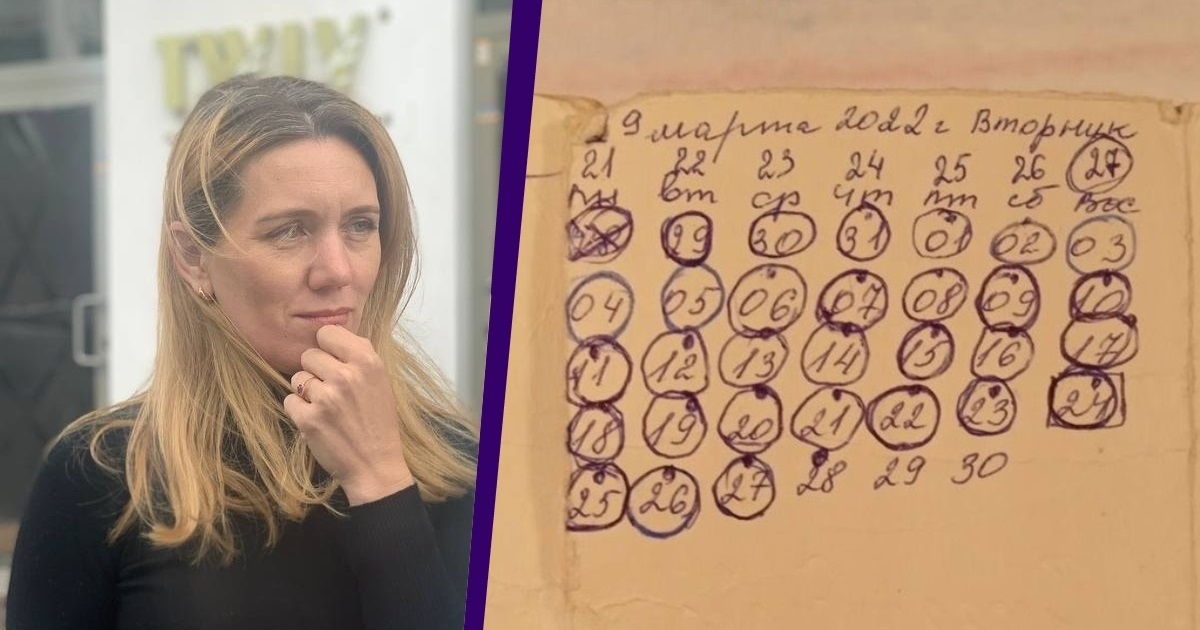

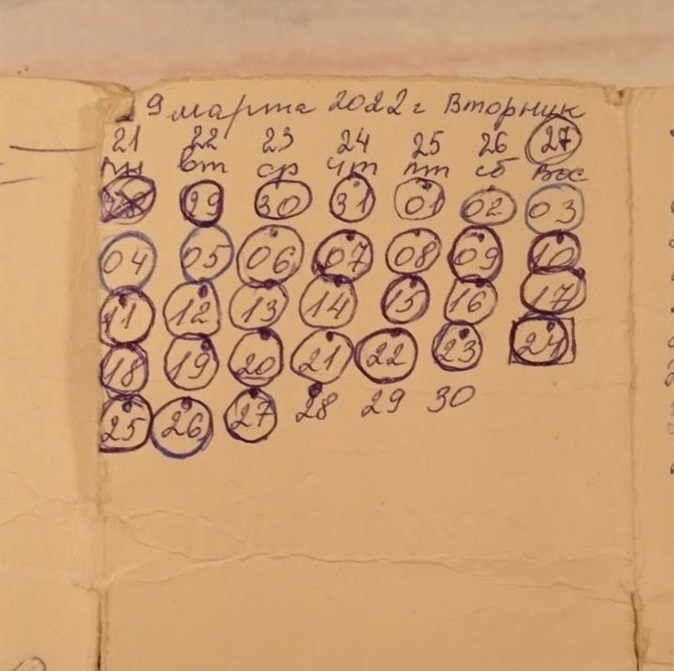

In captivity, they kept a calendar — writing the dates and days of the week on a tea pack

In captivity, they kept a calendar — writing the dates and days of the week on a tea pack

Judge Yulia Matveeva, who was detained together with her children and husband, was also in the cell with me. I ended up with her husband later in the Olenivka colony. And the third woman was the mother of an Azov battalion soldier, who had been there for 30 days and was waiting to be released every next day. Later I found out that she was released only on day 52.

There were shelves-beds with mattresses located around the perimeter of the cell, as well as a washbasin and a toilet. But the most depressing thing was the lack of visual contact with the outside space: a small 80x60 cm window was sealed. For the first few hours, the brain refused to accept the task: to endure this isolation in complete inactivity for 30 days. The only consolation was that it was warm there, something my body hadn’t felt since February 24...

At that time I managed to sneak a pack of cigarettes into the cell — that was a real gift for the girls. I shared all those precious in that space, but so ordinary, things with the girls: soap and shampoo. By the end of the day, they brought in another girl, an accountant from the National Guard. There were five of us, but only three beds.

To the Colony — In a Small Cell of a Prisoner Transport Vehicle

On the next day, I was called, bag and baggage. Taira quickly explained to me where I could be transferred. The Olenivka Colony was in the list of possible places. That's where I got on April 2. There I would exist for 100 days.

Not all of my things seized upon arrival at the detention center were returned. We also heard rude and insulting shouts, the military tied our hands with tape again, and again there was that terrible corridor surrounded by dogs and endless ringing of the alarm system. And a huge prisoner transport vehicle, inside which the space is divided into mini-cells accommodating from one to three people. I was in a solitary cell. A 80x45 cm space, kind of a punishment cell.

While we were on the way, the guard announced that we were going to the Olenivka Colony, where we would stay for 30 to 90 days. That would depend on the authorities that issued the detention protocols. He also said that military personnel and conscripts registered in any Ukrainian region except for Donetsk could expect to be released only after this region would become part of the Russian Federation.

We Were Just a Piece of Shit to the Colony Workers

We arrived. We were called one by one. There were six females and about 20 males in total. My name was called. Sunlight, air, steppe wind, and some poor two-story buildings, each with DPR flags, people dressed in different uniforms, everyone has weapons, dogs and gates...

The prison is made up of barracks, in which captured soldiers now live. In the middle of the barracks, there is a separate prison — a disciplinary isolation cell, where violators of the prison regime are kept. This is a separate building, which is like a strict cell with wooden bunks and stone floor, with cells, with a door, a public toilet inside, without water. In peacetime, for example, if a man was in the colony and had a fight with someone, he was thrown there for 15–20 days as punishment.

And I got just into such a cell. The whole space screamed of neglect and unusability: dirt, the stench of sewage, piercing cold, and cries for mercy from males being beaten. The workers themselves called this place “the pit.” The colony authorities believed that a woman who voluntarily, despite the threat to her life, saved people by taking them out of the war, should be in exactly such conditions.

Policewomen lived in the barracks, but I didn’t fall into their category. In fact, I had a category of “a peaceful resident detained for unknown reasons.” None of the colony employees told me anything — why I was there or how long I would stay there. They just laughed, called it filtering. Nobody spoke to me or other arrested volunteers. To them I was just a piece of shit. The colony employees said that it was filtering and they would release us in 10–15 days. It’s like “Don't worry, you’re not a military woman.”

We’ll Stay Here until the End of the War...

10 days passed. I asked to be allowed to speak with the colony head, I wanted to know when I’d be released. But the supervisors said: “Keep still and don't stick your neck out, the administrative protocol will soon end..."

The documents were issued on April 30, and from that date on I stayed in prison. I was supposed to be released on May 30, but two days before that date I was called and told that I would stay in the colony for another 30 days. And they asked me to sign just one piece of paper that said “I have no complaints against the colony.”

Of course, I had complaints. I made a scandal, I realized that my good behavior or silence wouldn’t reduce the term. The paper said I was detained not in Mangush, but in Volnovakha on April 28. Thus, I was given a newly issued document to sign. And thus, I was just then starting the new 30 days. I signed nothing. I was returned to the cell. Herewith, there were no interrogations, no investigator talked to me.

On June 7, they called me again, and again gave me a piece of paper to sign. Again, it said that my stay in the colony had been extended. The paper was dated May 30 and said that I had been detained in Volnovakha for 10 days. I started to explain when and where I’d been detained. The inspector said that couldn’t be so, he was very surprised. I signed that paper. According to that document, I was to be released on June 9.

On June 9, they called me to the headquarters, together with the girls from Azov, and took my fingerprints once again. I asked them who they were. They said they were employees of the Ministry of Justice of the DPR. I told them that was already the tenth procedure, that I had stayed there since the end of March and wanted to know when I’d be released. They promised to find out. At that time, rumors were already circulating in the prison that the detained volunteers had already received the status of prisoners of war.

On the same day, we were lined up in the yard when the deputy head of the prison walked by. I asked him why I wasn’t released that day according to the latest protocol on administrative detention dated May 30 and was replied: “Vorosheva, forget it, all administrative detainees have already been given the status of prisoners of war and you’ll stay here until the end of the war!” He said that Pushylin had issued some decree, according to which all the detained volunteers fall under the status of prisoners of war.

Bag and Baggage: Through Donetsk to the Netherlands

And then silence. Nobody called us anymore. As if we, volunteers, didn’t stay in the colony. And then we heard that social networks were writing about us. Our relatives created an information wave, noise. We weren’t forgotten, we were searched for. On July 4, the deputy head of the colony called me and said: "Bag and baggage."

I had to call at the Department for Combating Organized Crime in Donetsk to go through filtering and get my documents. Then through Zaporizhzhia, Kyiv, and Warsaw, I headed to the Netherlands.

A new life will start for Anna and her family in the Netherlands

A new life will start for Anna and her family in the Netherlands

While I was in captivity, my friend Alyona took care of my relatives — she found them a place to live and helped them with documents. The state supported the refugees from Mariupol and provided financial assistance. I’m very grateful for this to my friend, authorities, and caring citizens of the Netherlands. I really hope I will find refuge in this country for myself as well.