The only military-age man who fled the so-called DPR: the truth about the filtration

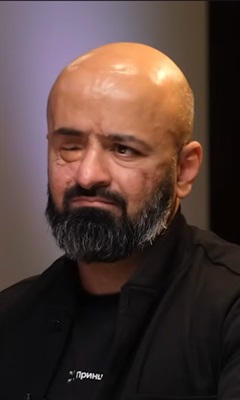

Maksym is 23. Although he is a registered Donetsk resident, he has been living in Volnovakha for eight years now. He was forced to move in here with his family when his hometown was occupied in 2014. In these years, Volnovakha had become his home away from home: he had been studying there, working in the creative industry, and hadn’t been going to move.

The Russian army and the militants of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic occupied Volnovakha in the middle of March. Maksym survived the shelling, living in a bomb shelter, interrogations, and filtration. While trying to get out of the occupied territories, he saw Donetsk for the first time since he had left. Maksym told us what residents of Volnovakha had to live through during the fighting and occupation.

More than 400 residents of the city were hiding in the hospital’s basement

On February 24, the residents of Volnovakha were divided into two categories: those who left the city and, therefore, stood in lines at the gas stations to buy some gasoline, and those who had decided to stay and thus stood in lines at ATMs and shops. None of those groups realized the scale of destruction which awaited the city.

February 25 was the most terrible day for me. In the late afternoon, the lights were turned out - and there was a sudden deadly quiet. No one moved around the city. We apprehended the attack to begin at any time.

It happened the next day. In the morning, machine guns could be heard; the city was being shelled. My family and I decided to leave our home and go to our relatives who live in another part of the city. While on our way, we saw plenty of burnt military equipment and vehicles.

Since February 27, Vodafone and Kyivstar mobile signal had been down all over the city. There was no water or electricity; gas was cut off a few days later. The invaders were shelling the city, and later on, air strikes began.

We moved to a makeshift bomb shelter which was located in the hospital for railway workers. 400 civilians and medics who were tending to the wounded lived in that dark and cramped basement. A surgeon and an anesthesiologist kept operating on the second floor despite the shelling.

The basement wasn’t suitable to accommodate people. It was a dark, poorly ventilated area where the elderly, children, and the wounded had to live.

We started knocking down the doors and taking out the garbage and junk. After that we laid mattresses on the floor to sleep on. Some guys went to the neighboring shop, which had already been broken into, and took as much food as they could. We cooked food on a campfire under the bombing.

When going outside, we saw our city in flames. We got the news only from each other. In a few days, we made up our minds to move in with our relatives, because we were going nuts from being in that basement.

My home had already been occupied by the militants

The next two weeks were pure hell. The shelling wouldn’t stop day or night. The occupiers hadn’t been able to cross the railway for more than 10 days because Ukrainian defenders had secured their position at the train depot.

During that period, the building had been attacked countless times with all sorts of weapons including mortars and air bombs. The houses situated near the enterprise went to utter ruin. I was told that there were lots of dead civilians lying in the streets in that neighborhood.

On March 14, the shelling subsided a bit, and people started to come outside and walk around the city, going home or to their relatives. My house was badly damaged by then; it was occupied by the gunmen. All the doors and windows were blown out; the heating pipes burst. The yard was hit several times. The occupiers conducted a sweep-up: they would go from door to door, searching for the Ukrainian military.

The “humanitarian aid”, groceries from Russia, started to be delivered to Volnovakha. However, one had to wait in line for hours and show one’s papers in order to get it. That “aid” was distributed either downtown or at the bus station, and we were never informed beforehand. It was like Russian roulette - everything depended on luck.

Many elderly people didn’t even know the humanitarian aid was being delivered; besides, not everyone who did know could go from one part of the city to another and stand in a queue for hours.

At first, they told us the humanitarian aid would be delivered monthly, but then the rhetoric changed. When someone asked where the humanitarian aid was, they’d say, “It has been shipped to Mariupol.”

Also, they brought bread to the Volnovakha district administration. It was handed out by a Chechen, who filmed the entire process. At first, there was a bathhouse downtown. The rescue forces of the so-called DPR secured the spot and let people make calls, but only to the Feniks mobile operator (mobile operator in the occupied Donetsk - Editors). However, it all came to an end in two weeks.

There appeared the profiteers who bought goods in Donetsk or Dokuchaievsk town and resold them in Volnovakha for triple price. They pumped hryvnias out of Volnovakha residents. If one wanted to convert hryvnias into rubles, the exchange rate was very low. 2 or 2.5 rubles were paid for 1 hryvnia depending on where you changed your money.

The fight for cutting in the filtration line

Now I know from experience what “filtration” is like, as well as many other residents of the occupied city. I know what one should go through to get that paper. One cannot travel without it inside the territory controlled by the so-called DPR militants.

I did manage to get this “document” after three weeks of endless standing in lines, first in Dokuchaievsk and then in Buhas village.

In order to get a permit in Dokuchaievsk, you need to sign up on a list and receive a number. Afterwards, you have to check in from 6:00 to 18:00 on a daily basis, confirming your presence. If you miss a roll call within three hours, you will be off the list.

In Dokuchaievsk, they could “filtrate” only 100-150 people per day. People from Mariupol were brought there and processed immediately, without waiting; then they would be sent to Russia.

When it was finally my turn to register, Volnovakha was temporarily locked down, and I lost my slot. Therefore, I had to undergo this procedure in Buhas. There was a rescue forces bus that traveled from Donetsk to Volnovakha; it picked up only 35 people at a time and took them to Buhas to go through filtration without queuing.

In order to get on that bus, one had to sign up on a list and wait one’s turn for nearly a week, coming downtown and checking the list, or one could try and get on the bus on the first-come-first-served basis.

People would start forming a queue at 2:00 a.m., despite the curfew. The most interesting things were happening when the two queues met and decided which one would go to Buhas. Fighting and arguing occurred every single day.

The very procedure of getting a permit was different in Dokuchaievsk and Buhas. In Dokuchaievsk, people were fingerprinted, had their IMEIs and the contents of cell phones checked, photos taken and passport data put on the file, while in Buhas, they didn’t even ask to look at the phones.

Going through the “filtration”, some people found themselves under close scrutiny of the so-called Ministry of State Security of the so-called DPR. The militants would check all their chats on the social media, contact lists, and the contents of their laptops. If you had been in active military service or served on the contract basis in the army, they took you in for questioning. That’s how they’d figure out who could be dangerous for the “republic”.

As for me, I had no trouble with that at all. I deleted all the messenger apps from my phone back on February 25 and thoroughly checked my contact list. Later on, I deleted all the photos and videos of the destruction in Volnovakha, leaving only my private photos.

Here’s a lifehack for those who want to keep the information safe during “filtration”. You can upload everything into one of your Telegram chats, delete the app on your devices, and when you are in a safe place again, you can download and reinstall the app.

They were surprised I hadn’t been taken away by then

After I had been issued a permit, I got to know that there were buses which traveled from Donetsk directly to Poland. The price of a single ticket is $330, or €300. I found a bus carrier who could take us from Volnovakha to Donetsk for a thousand hryvnias, and we went to the city I hadn’t seen for eight years.

Although all the people in the bus had their permits, we were stopped at Donetsk checkpoint and told that a separate permit for the vehicle itself was required. We caught a ride and were delivered to a hostel.

I had a negative vibe from Donetsk. It turned out that the city was frozen in 2014. There were only girls, women, and older people in the streets. If not yet mobilized, all the men liable to call-up have gone into hiding.

At 8:00 a.m. we boarded a bus and set off on a 72-hour journey to Poland. The route goes through Russia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

I felt uncomfortable: when we were leaving the occupied territories, I was the only military-age man. I don’t know how the hell I managed to make it through customs of the so-called DPR and Russia with my Donetsk registration. Even my fellow passengers were surprised and asked whether I wasn’t afraid to go and why I hadn’t been taken away by then.

Passing through the customs on Russia’s border with the so-called DPR took us approximately two hours. As for the Russo–Latvian border, it took around seven hours. The first thing you see at the Latvian customs is an announcement reading, “Anyone who has suffered from the Russian aggression can report the crimes committed by Russians.” The Latvian border guards were very friendly; I felt safe and relaxed. After a 12-hour ride I was finally in Warsaw.

A strange country, strange language, no plans for the future - this is what awaits me here. However, I’m glad I managed to get out of my city, which had been occupied.

I understand that first and foremost, I have to unwind a little both emotionally and physically, and take some time to relax. My body requires a quiet, head-down kind of life after the 70 days spent without water, electricity, or gas and under the shelling. Afterwards, I’ll need to take care of the paperwork required for employment and start looking for a job, simultaneously learning the language and adapting to the new country.

Volnovakha and my house have been destroyed, so I’ll need to find a new place for myself in this world.