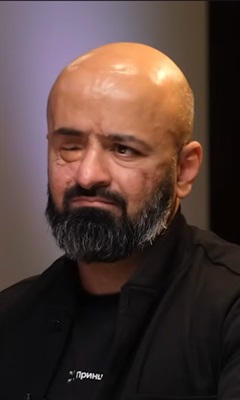

The sight of food shelves made him cry. "A guy with a new face" Vlad Oliinyk after Mariupol

Fortunately, the couple managed to escape from the city destroyed by the Russian army. Now they are in Tbilisi, where they told us their story.

We also want to remind you that we’ve already told about Vlad before the full-scale invasion of the Russian army into Ukraine: he had an operation in Kyiv, a facial reconstruction. The man then returned to Mariupol, waiting for the birth of his first child and his second operation.

I thought that there would just be shootings outside of the city — and that would be it

But the situation in Mariupol took a very different course — the cruelest one. We were living in constant fear till the end of February, and on March 1, when the explosions got louder, we decided to evacuate. We called a person who could help us move and agreed to meet at the store called “1,000 Trifles” near Svoboda square. We came at the arranged time and day and started to wait. We had been standing there for about two hours when the central market got shelled by “Grads.” It was about 1 kilometer from our location. We heard people screaming; we saw everyone running away.

I gathered concrete dumpsters and made some kind of a shield from debris while we continued to wait for the driver. But he didn’t come. Mariupol was closed.

On our way home, we saw a dead body on the city streets for the first time. It was a woman. She was lying on the ground, not yet covered with a sheet. I’d never seen a dead person lying in the streets before. It was horrifying.

Mariupol was closed on March 1. Copyright: Evhen Maloletka

Mariupol was closed on March 1. Copyright: Evhen Maloletka

We were worried about our baby

We ran home and discovered that the electricity had been cut off, and the water was barely dripping. We still had a mobile signal, so we texted our parents that we couldn’t get out. Then everything was gone: mobile signal, heating, water, and electricity. The only utility left was gas.

It was the beginning of the most horrifying days of our lives, of the lives of everyone who didn’t leave Mariupol. With every passing hour, it was getting worse, and colder.

Karina and I were in a critical condition. But most of all, we were worried about the baby. At first, we were sleeping in our apartment. Then we heard the air bombs falling nearby, moved to the hallway, and put our mattresses there. It was on March 4.

We ran out of water on March 7. There was free water, distributed nearby. I got in line at about 7 a.m. and stood there till 7 p.m., yet I failed to get any water. There were about a thousand people in line, and it’s no exaggeration. So many people and only one water truck. On that day, our gas was cut off, and people started searching the streets for tree branches to make an open fire and cook their meals.

I don’t remember which day it was; I went outside to make tea. At that moment, an aircraft flew over my head. I can’t say for sure which one it was, but my neighbors said it was Su-24 (Russian tactical front-line bomber). I heard explosions about 100 meters (328 ft) from where I was heating water. I saw a metal booth and ran to it. I tried to make a trench, digging the ground with my bare hands. A nearby apartment building was entirely on fire, all the twelve floors from the very foundation. Other buildings turned into mere empty shells.

I can’teven imagine how many people died then. My neighbors said that bodies, torn in parts, were lying on the ground next to the ruins.

The officials escaped; they abandoned the locals

After this, we lost any desire to cook food on an open fire. We ate only cold meals — the ones we had prepared before. We also had some meat preserves and cookies. We tried to make our food last as long as possible because we didn’t know how long we would have to stay there. Then, in addition to the airplanes, there came the tanks. They drove through our

streets. One day I looked out of the window — just for a moment — and saw something hit the apartment building next to ours. The explosion was so intense that it broke the windows in our other room.

We had neither a mobile signal nor a possibility to get any news. The only thing we knew was that the local officials had left. What kind of people would save themselves, not warning the local people about the danger?

Moving to the basement

On March 14, we saw people going down to the basement: the Packing Department of the Confectionery Factory was located on the ground floor of our apartment building. We also decided to go down there. We took our documents, the essentials, and a mattress. We didn’t sleep in our apartment anymore. We would just run up there to grab some food or some items. Only 20 meters (66 ft) separated the basement from the apartment, but I prepared for each journey as if I were to climb Everest.

There were eight more people in the basement, including two kids. The youngest one was three years old. The boy’s parents went to work in Poland and couldn’t return.

We cooked food on an open fire in the remains of a neighboring building that looked like a shed with concrete walls. One day, I had just reached a wall when the shelling from “Grad” began ten meters from me. The blast wave hit but didn’t injure me, fortunately. I was lucky, but 20 people died then and there, including children.

Absolute hell started a bit later. We forgot what silence meant. Explosions and shellings were all we heard. People were screaming and crying.

I found pasta and cheese in the burned warehouse

On March 22, the Russian Guard came to our basement. They started checking our passports, asking us who we were. Then they said, “We don’t wish you harm; you may ask us for help if you need it.”

While the Ukrainian military was on our streets, Russians shelled us with every possible weapon. As soon as the Russians and “DNR” [“Donetsk People’s Republic – temporarily occupied territory of Donetsk region”] military occupied us, the shelling stopped. I’m saying this just for the analysis because some people were spreading rumors that civilians couldn’t leave the city, that the Armed Forces of Ukraine were allegedly blocking the roads and turning everyone back to the city.

Vlad and Karina got married in the fall of 2021. Photo: Family archive

Vlad and Karina got married in the fall of 2021. Photo: Family archive

We were running out of food. We heard rumors that the “DNR” soldiers found warehouses with food and were giving it away. So I went there. It was the first time I went to the downtown since the beginning of the war. I can’t put into words what I saw.

All buildings were in ruins. There were dead bodies lying in the streets. There were also graves right in the yards. People had to be buried somewhere, but the Starokrymskyi cemetery, one of the biggest ones in Europe, was destroyed. No one was allowed there because of the constant shootings.

The food warehouse was two kilometers away. I came and saw immense crowds of people. The warehouses had been shelled; there had been fires. Together with other people, I dug through the debris, looking for intact food. I found pasta, several jars of beans, and cheese — there was a lot of cheese.

We were going to Russia but came to Donetsk instead

We heard about “greed corridors” from some woman we met in the street. We took the little food we had, some clothes, and gadgets from our apartment and went to the checkpoint near the Starokrymskyi cemetery. When we passed the “Port City” mall, the neighboring street was shelled with “Grads.” The explosions were very close, about 300 meters away.

We started running non-stop. When we reached the checkpoint, a car drove up; it was utterly slashed by shell fragments. Inside the car, a person was screaming from pain. The driver was looking for pain killers, asking the military for them, but they had none.

“Where are the evacuation buses? No matter where to,” I asked them, but they just shrugged their shoulders. My heart dropped. Then, a man showed us a bus standing along the road, about 500 meters away (1640 ft). We started running again.

“The ones who had come earlier said that they had one meal a day — some porridge with preserved meat and a piece of bread. And tea. 3-4 cups a day. The school had electricity to charge the phones. And it had heating. I took my coat off for the first time that month.”

They were making lists of people willing to go to Rostov. We wanted to go to Donetsk, but that was not an option. A free trip was only to Russia.

The drivers asked for unbelievable sums of money to take people to Berdiansk — starting from 2,5 thousand hryvnias ($83) for one place. How could people, who spent an entire month in a besieged city, have this money? Then, a line of buses came. We asked the first bus, “Where to?” — “Taganrog!” The second one, “Where to?” — “Rostov!” The third one, “Where to?” “To Bezimenne”. We got on one of the buses without a precise understanding of our destination.

I talked to the driver, who was from Kuban. He worked as a bus driver in his city. He and some other bus drivers were summoned at night and directed first to Rostov, then to the Donetsk region.

Karina and Vlad at the refugee camp in Nikolske. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

Karina and Vlad at the refugee camp in Nikolske. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

We were going along ruined roads and fields. At some point, a bus driving in front of us drove over the steel anti-tank “hedgehog” and damaged the radiator. People from that bus were placed on other buses. Then we reached Novoazovsk. We spent the whole night at the border of the “DNR” and Russia.

I got tired, came up to the Russian border guard, and asked why everything was taking so long. I asked whether we could cross the border on foot. When I didn’t get any response, I asked the “DNR” border guard whether there was a taxi nearby to go to Donetsk. We collected our things to take the risk and go to Donetsk. We paid 5 thousand rubles ($75).

The driver had the letter “Z” on his car. He said it meant “For peaZe” [For peace]. He said, “If Russia didn’t do this to Mariupol, it would have happened to Donetsk.” Later, I heard this statement in Donetsk several times.

I saw a store and burst into tears

Do you know how little a person needs to be happy? We took a bath in Donetsk; the bathwater became black like oil. We put on some clean clothes, had a good meal, and went to bed.

Then we went to the supermarket. Seeing food on the shelves brought me to tears, I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t stop for some time.

After pulling ourselves together and resting, we had to go to the District Department of Internal Affairs. We had to undergo the “filtration”. The taxi driver told us about it, which was later confirmed by our acquaintances. At the department of Kalininskyi district, they told us they didn’t know anything about “filtration” or what to do with refugees. They sent us to another police department at Leninskyi district. It was full of people. They interrogated us and investigated the pictures on our phones carefully. They looked through my Telegram; I had subscribed to the official channel of Zelenskyi, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, and several Ukrainian news channels. They asked why I had subscribed to these channels and whether we planned to leave Donetsk. I said that we wanted to go to Krasnodar and then to Europe. Then he asked, “Why don’t you want to stay in Krasnodar?” I said that the war would soon start there. They tried to convince me that Kyiv had almost fallen… After the interrogation, they took pictures of us and took our fingerprints. I felt like a criminal from a movie because I saw such procedures only on screen.

Food that Vlad bought in Donetsk. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

Food that Vlad bought in Donetsk. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

Letting go of the horrific memories and planning the future

On March 24, we took a bus to Krasnodar and then went to Tbilisi. We were interrogated on the Russian border, “Where? Why?” They exhausted us and then let go. I forgot to mention that we had our pet chinchilla named Bak with us all this time. And on the Georgian border, we were asked whether the rodent had a passport. Of course, it didn’t. We didn’t know that our lives would change so drastically. We said that we didn’t have a pet passport and that we were refugees from Mariupol. The Georgian border guard let us through with no further questions. I started crying once again: we had been tortured with the interrogation on the

Russian border for no less than an hour and treated horribly. Crossing the Georgian border took us only 5 minutes.

Vlad and his wife went to Georgia; they are getting help there. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

Vlad and his wife went to Georgia; they are getting help there. Copyright: Vlad Oliinyk

We are renting an apartment in Tbilisi. For the first five days, we lived in a hotel for free and had free meals. Karina got registered with a local hospital without paying for tests or the ultrasound. We are trying to let the horrific memories go. The next step is planning the future.